One Health

Article

|Published

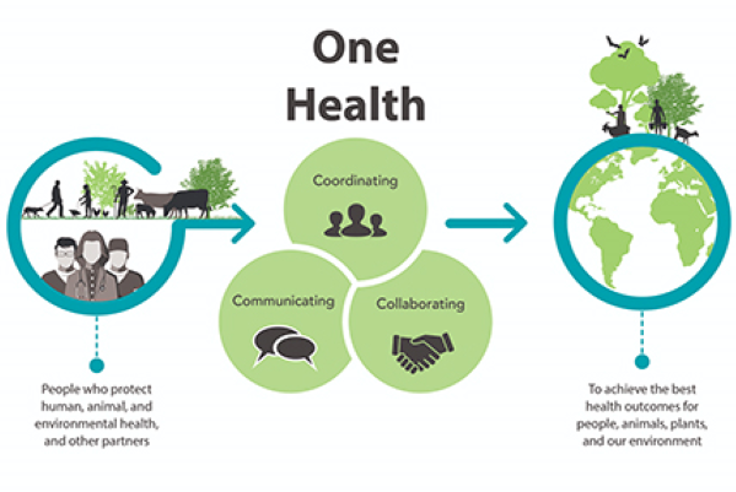

'One Health' is an approach for designing and implementing programmes, policies, legislation and research where multiple sectors communicate and work together to achieve better public health outcomes.

What is One Health?

'One Health' is an approach for designing and implementing programmes, policies, legislation and research where multiple sectors communicate and work together to achieve better public health outcomes.[i] WHO also states that a One Health approach is particularly relevant for working areas like:

- food safety,

- the control of zoonoses, diseases that transmit between animals and humans, such as influenza, rabies and Rift Valley Fever

- in combating antibiotic resistance, when bacteria mutate after exposure to antibiotics and become more difficult to treat.[ii]

Combating emerging health threats, foodborne diseases, zoonoses and antibiotic resistance are central for One Health working areas. Moreover, One Health closely relates to climate change and environmental studies. Therefore, public health organisations need to be active both in the health systems in the strict sense of the term as well as in non-health sectors.

In the health sector strategies, we need enhanced and targeted epidemiological and entomological surveillance by developing epidemic early warning systems using climate scenarios. Measures in non-health sectors, such as meteorology, civil defence and environmental sanitation, contribute to better preparedness and decrease the risk of infection under climate change.[iii]

In Norway, the Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH) collaborates closely with other organisations like Norwegian Veterinary Institute and Norwegian Food Safety Agency, in order to achieve better outcomes in prevention and investigation of infectious diseases outbreaks. In cooperation with the Norwegian Directorate of Health, the NIPH provides advice to Ministries (Ministry of Health and Care Services, Ministry of Climate and Environment and Ministry of Agriculture and Food) on development of better policies and legislation within public health.

Our One Health Approach does not stop there, the NIPH also works towards regions and local health services (municipal medical officers) as well as internationally building sustainable partnerships in Europe, European Agencies (ECDC, EMA and EFSA) and beyond with other important global stakeholders (WHO, FAO, OIE).[iv][v]

Historical Perspective

The One Health concept is already apparent in the work "On Airs, Waters, and Places" from Hippocrates (460 - 370 BCE) promoting public health dependence on a clean environment.[vii]

Later, increased travel between continents not only contributed to international trade development but also to outbreaks of animal pests leading to several pandemics of plague. The most well-known is the Black Death that hit Europe in the 14th century, and resulting in the death of a third of the European population (more than 25 million people).[viii] [ix] [x] [xi] Plague transmission is generally from infected fleas carried by rodents or rarely, in clothing or grain, but may also occur through eating contaminated animals, physical contact with infected victims, or direct inhalation of infectious respiratory droplets.[xii] [xiii] [xiv] [xv]

Since then, humans went through several pandemics caused by transmission of disease by animals like Spanish flu[xvi] [xvii]or from polluted environments, namely water in cholera times[xviii].

Today, humanity is facing another pandemic that has taken the lives of over 1.46 million people (30th November 2020 statistics)[xix]. Similarly, with many other pandemics, COVID-19 is transmitted by infected animals and humans where good hygiene plays an important role.[xx]

A health threat anywhere is a health threat everywhere

![Illustration of Global aviation network: Air traffic to most places in Africa, regions of South America, and parts of central Asia is low. If travel increases in these regions, additional introductions of vector-borne pathogens are probable. [xxi] Illustration of Global aviation network](/contentassets/a95f6469bee4468c81a046cbce2f97bb/globat-luftfartsnettverk.png?preset=mainbodywidth&maxwidth=970&width=970)

We live in an interconnected world where diseases know no borders and are spreading farther and faster than ever before. A health threat anywhere is a health threat everywhere. Nearly 70% of the world’s governments are underprepared to manage and control health emergencies, leaving gaps that make us all vulnerable to epidemics. Outbreaks have an enormous social and economic impact locally and globally. SARS and Ebola each had a devastating economic impact, causing a loss in growth and revenues in the order of billions of U.S. dollars.[xxii] The COVID-19 pandemic has so far claimed over one million of lives globally [xxiii]and the socioeconomic impact is still unknown.

Nevertheless, we should also consider possible source of disease like animals not only as a threat but also as an opportunity in prevention and treatment. Some animals carry disease without having any symptoms.[xxiv] More research on why animals are better adjusted to pathogens[xxv] could have breakthrough results in future medicine and a positive outcome on biodiversity[xxvi] [xxvii].

How does the NIPH contribute to One Health?

The NIPH is involved in number of projects where One Health plays a central role. More information such initiatives can be found on the following links:

The One Health European Joint Programme (OHEJP), https://onehealthejp.eu/about/

Tidenes største En- helse satsing finansiert fra EUs Horisont 2020, (only in Norwegian version)

Norwegian Global Health Preparedness Programme, https://www.fhi.no/globalassets/dokumenterfiler/global-helse/ghpp/poster-_ghpp.pdf