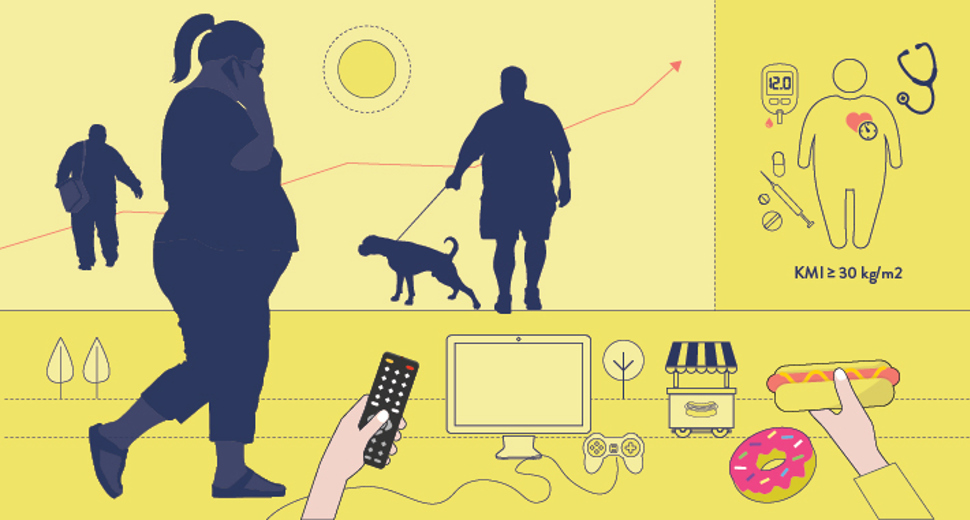

Overweight and obesity in Norway

Most of the adult population is overweight or obese. Among children, the overall proportion of overweight and obesity appears to have stabilised. Since the 1970s, there has been a strong increase in the prevalence of overweight and obesity, which is probably related to the environment we live in. Obesity is associated with an increased risk of several non-communicable diseases. Arrangements for a healthy diet and physical activity can help preventing obesity in the population.

Main Points

- The proportion with overweight and obesity in the population has increased over the past 50-60 years. However, among children and adolescents, the proportion of those who are overweight and obese has remained relatively stable since 2010.

- Overall, between 15 and 21 per cent of children and adolescents (8-15 years) are overweight or obese (about 1 in 6).

- Based on data from the Health Studies in Trøndelag and Tromsø, around 1 in 4 men and women in the age group 40-49 are obese.

- The overall proportion of overweight and obesity varies by region and level of education.

- It is mainly obesity that is associated with increased health risks. A high BMI contributes to an estimated 2,800 annual deaths in Norway and is associated with several conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and other chronic diseases.

About overweight and obesity

Overweight and obesity are conditions with an excess of body fat. There are several measurements for overweight and obesity:

Body mass index (BMI) is the most used measurement for weight ratios in the population. BMI is calculated by dividing body weight by the square of body height - kg/(height * height). For adults, these limits apply:

- BMI of 18.5-24.9 kg/m2 is defined as normal weight.

- BMI of 25.0-29.9 kg/m2 is defined as overweight.

- BMI of 30 kg/m2 and higher is defined as obesity.

For children (5-18 years), separate BMI limits are used to define different categories of weight status.

Waist circumference (waist measurement) is used to determine whether a person has abdominal obesity. The waist circumference is taken using a tape measure around the waist at navel height. Waist circumference is used together with BMI to assess health risk and can give a better indication of the distribution of body fat than BMI.

For adults, a waist circumference of over 88 centimetres for women and over 102 centimetres for men is defined as abdominal obesity.

Overweight and obesity among children and adolescents

Results from mapping studies show that overall, between 15 and 21 per cent of children and adolescents are overweight including obesity, that is about 1 in 6 (Júlíusson et al., 2010; Øvrebø et al., 2021; NIPH, 2021a; NIPH, 2023).

The latest national prevalence figures we have for overweight and obesity among children and adolescents are from four different studies carried out between 2015 and 2019.

Results from the Child Growth Study show that:

- Among third graders measured in 2019, 13 per cent were overweight, while 4 per cent were obese.

- Among the girls, 15 per cent were overweight and 4 per cent obese.

- Among the boys, 11 per cent were overweight and 3 per cent obese (NIPH, 2023).

The third graders were 7-8 years old when weight and height were measured in the autumn of third grade.

Results from the other national surveys show that:

- Among fourth graders measured in 2018 in the survey of physical activity (UngKan), which also includes body measurements, 18 per cent were overweight and 3 per cent were obese. There were no clear gender differences among these 9-year-olds (NIPH, 2021a).

- Among eighth graders measured in 2017 in the Youth Growth Study, 13 per cent were overweight and 3 percent were obese. There were also no gender differences in overweight or obesity among the 13-year-olds (Øvrebø et al., 2021).

- Among tenth graders measured in 2018 in the UngKan survey, 14 per cent were overweight and 3 per cent were obese. The proportion with overweight among these 15-year-olds was higher among girls than boys. 17 per cent of the girls were overweight, and 5 per cent were obese. For the boys, 11 per cent were overweight and 2 per cent were obese (NIPH, 2021a).

Trends over time for children and adolescents

The proportion of overweight children probably increased towards the start of the 2000s (Juliusson et al., 2007). The Child Growth Study has investigated the proportion of overweight and obesity among third graders (7-8-year-olds) in the period 2008 to 2019. The results indicate that the trend has been relatively stable since 2012, but there are no signs of a decline, see figure 1. Figures from the UngKan study shows a stable trend for the proportion of overweight and obesity among 9-year-olds from 2011 to 2018, see figure 2.

The proportion of overweight and obese adolescents has increased over the past 50 years, but since 2011 there has been no indication of an increase among the 15-year-olds in the UngKan study, see figure 2. The proportion with overweight among 15-year-old boys was 12 per cent in 2011 and 11 per cent in 2018, while the proportion with obesity was 3 per cent in 2011 and 2 per cent in 2018. Among the 15-year-old girls, 19 per cent were overweight in 2011 and 17 per cent in 2018, but the proportion with obesity was somewhat higher among the girls in 2018 (5 per cent) than in 2011 (3 per cent) (NIPH, 2021a).

Some studies indicate that over a longer period, the average waist circumference among adolescents has increased more than the average BMI (McCarthy, Jarrett, Emmett, & Rogers, 2005), also in Norway (Kolle et al., 2009). However, there were no changes in waist circumference from 2011 to 2018 among children and adolescents who participated in UngKan (Steene-Johannessen et al., 2019). In the Child Growth Study, the proportion with abdominal obesity has been relatively stable in the period from 2008 to 2019, see figure 3.

Results from the Trøndelag Health Study (Youth-HUNT4) among 13-19-year-olds (lower secondary school and upper secondary school in the former Nord-Trøndelag county) in 2017-2019 show a slightly higher proportion of overweight and obesity than in the national surveys. 18 per cent of girls and 17 per cent of boys were overweight, while around 7 per cent were obese. Overall, about 1 in 4 adolescents aged 13 to 19 were overweight and obese in Trøndelag (Rangul & Kvaløy, 2020).

Divided by lower secondary school and upper secondary school, the proportion with overweight in lower secondary schools was 15 per cent among boys and 17 per cent among girls, and the proportion with obesity was 6 per cent for boys and 4 per cent for girls. The proportion with overweight in upper secondary school was 18 per cent for boys and 20 per cent for girls, and the proportion with obesity was 9 per cent for boys and 8 per cent for girls.

Figures 4a and 4b show attendance figures for lower secondary school and upper secondary school separately from 1995-1997 to 2017-2019. For boys, the proportion with overweight and obesity was stable from 2006-2008 to 2017-2019, see figure 4a, but this does not apply to girls, see figure 4b.

Results from the Fit Futures 2 health survey in 2012-2013 among upper secondary school students in Tromsø and Balsfjord municipality show that a total of 21 per cent of young women and 28 per cent of young men aged 18-20 were overweight or obese (Evensen et al., 2017).

We lack measurements of height and weight among children and adolescents in Norway after the COVID-19 pandemic, so further trends are somewhat uncertain. Sessional data from the Armed Forces indicate that the proportion of overweight and obesity has remained relatively stable among both boys and girls in recent years, see figure 5 (NIPH, 2023). The data are self-reported and should be interpreted with caution.

Overweight and obesity among adults

The Tromsø Study and the Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT, in the former Nord-Trøndelag county) report that most adults are either overweight or obese. We do not have national figures based on measured height and weight, but these two studies from the period 2015-2016 (Løvsletten et al., 2020) and 2017-2019 (Erik R. Sund, unpublished data) show that:

- About 23 per cent of men and 42 per cent of women aged 40-49 have a BMI below 25.

- Most men and women are therefore overweight or obese. The proportion is greatest among men.

- Around 27 per cent of men and 25 per cent of women aged 40–49 are obese, see Figure 6.

- Although there is overall a greater proportion of men than women who are obese, the proportion with class 2 or class 3 obesity (BMI ≥ 35 and 40 kg/m2) is slightly higher among women than among men (8.2 per cent among women and 6.8 per cent among men), see figure 6.

Adults and BMI

BMI = body mass index, which is an expression of weight in relation to body height.

BMI is calculated by dividing body weight by body height squared - kg/(m x m).

Overweight:

BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2. A person who is 170 cm tall and weighs 73 kg has just passed the limit for overweight of 25 kg/m2.

Obesity:

BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2

Obesity is divided into three subgroups:

- Obesity class 1: BMI 30–34 kg/m2. Means in practice that the weight is over 87 kg for a person who is 170 cm tall.

- Obesity class 2: BMI 35-39 kg/m2. Means in practice that the weight is over 101 kg for a person who is 170 cm tall.

- Obesity class 3: BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2. In practice, this means that the weight is over 116 kg for a person who is 170 cm tall.

The term morbid obesity is used for BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 or BMI ≥ 35 combined with at least one comorbidity.

BMI and waist circumference work well as measures of overweight and obesity in a population, but when applied to individuals they can sometimes be misleading. For example, people with a lot of muscle and people who have lost body height can be defined as overweight even though they have a normal amount of body fat in their body. Analyses in the Tromsø study show good agreement between simple body measurements, such as BMI and waist circumference, and more accurate measurements of overweight and obesity (Lundblad et al., 2021a).

If we extrapolate the results to the entire population in the 40-49 age group, around 53,000 people have a BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 (class 2 or class 3 obesity).

Waist circumference and the proportion with abdominal obesity have also increased over time, and the increase has been greater in younger compared to older adults (Løvsletten et al., 2020; Midthjell et al., 2013).

A study from the Tromsø study 2001-2016 of trends over time in general obesity and abdominal obesity measured with more accurate measurement methods (DXA measurements) shows that the proportion of body fat and the proportion of visceral fat (abdominal fat) increased in the adult population. There was a greater increase in body fat in the period 2007-2016 compared with the period 2001-2007, and a greater increase among the younger (40-49 years) compared with the older, especially among women (Lundblad et al., 2021b).

Data from HUNT indicate that among adults with a BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2, almost half (40–50 per cent) are morbidly obese, meaning that they either have co-morbidities or a BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 (personal communication, Kristian Midthjell). See also the fact box above about the different categories of obesity.

Trends over time among adults

The proportion of overweight and obese adults has increased over the past 50 years.

Men:

- At the end of the 1960s, only approximately five per cent of Norwegian men in their 40s were obese.

- Since around 1970, the average weight has increased continuously.

Women:

- Among women, the proportion with obesity was reduced from 13 to 7 per cent in the period from the 1960s to the end of the 1970s.

- Since around 1980, the average weight increased in the same way as for men (Meyer & Tverdal, 2005)

Figure 7a and b shows how the prevalence of obesity has increased among men and women in the Tromsø Study and in the Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT). The trend has been somewhat different among age groups: For those aged between 40 and 49, there has been a strong increase in the last decades for both sexes. Women between the ages of 60 and 69 started with a higher proportion of obesity compared to men, but the proportion has remained relatively stable over time. Among men, the proportion with obesity has increased, and is now roughly at the same level as among women.

Differences between groups in the population

Geographical differences

The proportion of overweight children is 50 per cent higher in rural areas than in cities. The percentage with abdominal obesity follows the same pattern (Biehl et al., 2013).

The prevalence of overweight and obesity among children is highest in Health Region North and lowest in Health Region South East, according to measurements from the Child Growth Study and the Youth Growth Study (NIPH, 2014; Øvrebø et al., 2021).

Among 17-year-olds, the proportion with overweight and obesity is highest in Nordland and Troms and Finnmark, and lowest in Oslo, see figure 8 (NIPH, 2023). Self-reported data from the National Public Health Survey show similar differences in adults in figure 9 (Abel & Totland, 2021).

The Sami population

Data from the Sami population were collected from the SAMINOR 1 study in 2003-2004 and SAMINOR 2 in 2012-2014. Both health studies took place in a region with Sami and non-Sami populations.

The results show a general high prevalence of obesity among both Sami and non-Sami participants of both sexes. A comparison between the studies in 2003/2004 and 2012/2014 shows that the proportion with obesity has increased both among Sami and non-Sami men, while the proportion has stabilised or decreased for women (Jacobsen, Melhus, Kvaløy & Broderstad, 2022).

Abdominal obesity has increased both among Sami and non-Sami men and women (Jacobsen, Melhus, Kvaløy & Broderstad, 2022; Michalsen, Kvaløy, Svartberg, Siri, Melhus & Broderstad, 2019). Figures from 2003–2004 show that:

- a higher proportion of Sami than non-Sami men had BMI ≥30 while there was a lower proportion with abdominal obesity (waist circumference ≥102 cm)

- among Sami women, there was a higher proportion with both obesity measured with BMI and with abdominal obesity than in non-Sami women (waist circumference: ≥ 88 cm) (Nystad, Melhus, Brustad, & Lund, 2010).

Data from 2012-14 indicate the same ethnic differences as ten years earlier. (Jacobsen, Melhus, Kvaløy & Broderstad, 2022).

Analyses of those who attended both SAMINOR 1 and SAMINOR 2 show that the younger participants had gained more weight than the older ones in the ten years that had elapsed between the surveys. This applied to both Sami and non-Sami women and men (Jacobsen et al., 2020).

One reason for the higher proportion of obesity among Sami may be that Sami participants in SAMINOR are on average around 6–7 cm shorter than non-Sami participants and that the calculation of BMI does not fully take this into account. It is therefore uncertain to what extent the higher BMI measured among Sami men and women reflects a higher degree of obesity (Michalsen, Coucheron, Kvaløy & Melhus, 2021; Siri & Michalsen 2021.).

The immigrant population

Self-reported data from Statistics Norway's living conditions survey among immigrants in 2016 showed that the prevalence of overweight and obesity varies significantly between different groups of immigrants. Compared to the general Norwegian population, both women and men from Pakistan, Iraq, Kosovo and Turkey, as well as women from Somalia and men from Poland and Bosnia-Herzegovina had a clearly higher prevalence of overweight and obesity. Women and men from Vietnam had the lowest prevalence (Kjøllesdal et al., 2019). It has previously been shown that women from Sri Lanka and Pakistan have a high prevalence of abdominal obesity as well as having a high prevalence of diabetes (NIPH, 2008).

Variation by education and family situation

The prevalence of overweight and obesity varies with education and family situation.

Adults: Self-reported data from the National Public Health Survey 2020 shows clear educational differences in obesity with nearly twice as high prevalence among those with lower secondary /upper secondary education compared to people with 4 years or more of college/university education (figure 10).

Children and adolescents: There are also socioeconomic differences in overweight and obesity among children. The proportion of overweight is 30 per cent higher among children of mothers with lower education than among children of mothers with higher education. The percentage with abdominal obesity follows the same pattern (Biehl, 2013). Social inequality in children's BMI is already evident from infancy (Mekonnen et al., 2021).

In the Child Growth Study 2010, the proportion with overweight and obesity was over 50 per cent higher among children with divorced parents compared to children with married parents (Biehl, 2014).

Among 15-year-olds, we also see similar differences between children with parents with lower and higher education (Norwegian Directorate of Health, 2012).

International differences

The weight increase that we have seen among children and adults in Norway is part of an international trend in which the proportion of overweight or obesity is increasing in many countries. For children, however, there are signs that the rising trend has levelled off in some high-income countries (NCD Risk Factor Collaboration, 2017).

Among adults, data from EUROSTAT (where Norwegian data are collected by Statistics Sweden) indicate that the prevalence of obesity is among the lowest in Europe (figure 11).

It is important to point out that this is based on self-reported weight and height, and not measured values. This will result in a somewhat lower prevalence of obesity, but the strength of the comparison across Europe is that the data collection is performed in the same way in all countries.

In southern European countries, there is a much higher proportion of overweight and obese children than in Norway and other Nordic countries (Spinelli et al., 2021), see figure 12.

Health risks associated with obesity

Obesity increases the risk of developing some diseases and conditions (Directorate of Health, 2011; WHO, 2022), including:

- Type 2 diabetes

- cardiovascular disease. Despite the population’s weight having increased, the incidence of cardiovascular disease has decreased. One of the reasons for this may be favourable trends in cholesterol and other fatty substances in the blood, decreases in blood pressure and fewer smokers (NIPH, 2021b).

- certain types of cancer

- stopping breathing at night (sleep apnoea)

- osteoarthritis of the hip and knee

- stigma, mental disorders and discontent

However, the risk of osteoporosis and fracture is lower among people with obesity than in lean people (Søgaard, 2016).

Health risks among children

- Overweight and obesity among children and adolescents are linked to several health consequences in both the short and long term.

- Children who are overweight and obese have an increased risk of being overweight and obese as adults, with the consequences this entails for health (Simmonds, Llewellyn, Owen, & Woolacott, 2016).

- Being obese as a child can also lead to health consequences such as type 2 diabetes, asthma, musculoskeletal problems, risk factors for cardiovascular disease including high blood pressure and unfavourable lipids in the blood, as well as psychological challenges (Pulgarón, 2013; Reilly & Kelly, 2011; Sinha et al., 2002; Weiss et al., 2004).

Disease burden and death

A high BMI is an important indicator of disease burden in the population. In the 10 years from 2009 to 2019, the burden of disease linked to a high BMI increased by 12.8 per cent (IHME, 2022a).

In 2019, high BMI contributed to an estimated 5 million deaths worldwide, and around 2,800 deaths in Norway (IHME, 2022b). This corresponds to nearly 7 per cent of the deaths in Norway.

Among adults, it appears that abdominal obesity is more strongly associated with diseases such as type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases than is the case for general obesity (BMI over 30). Among children, abdominal obesity is also seen in connection with an increased risk of these diseases (Maffeis, Banzato, & Talamini, 2008).

Low weight is also a problem, especially among the elderly, and in the over-65 age group we find the lowest mortality with a slightly higher BMI than in younger people (Kvamme et al., 2012).

Factors that can increase the risk of overweight and obesity

Birth weight and weight gain in early childhood

High birth weight has the strongest association with the development of obesity in adulthood if the parents have a high BMI (Glavin et al., 2014; Kristiansen et al., 2015), otherwise it appears that there is only a small association between high birth weight and development of obesity in adulthood (Brisbois, Farmer, & McCargar, 2012; Evensen et al., 2017). It may therefore indicate that parental weight is more significant for the development of obesity than the birth weight of the child.

From the age of two, obesity in childhood is clearly associated with increased risk of obesity in adulthood (Evensen et al., 2017) (Glavin et al., 2014) (Johannsson, Arngrimsson, Thorsdottir, & Sveinsson, 2006) (Kvaavik, Tell, & Klepp, 2003) (Magarey, Daniels, Boulton, & Cockington, 2003) (Evensen, Wilsgaard, Furberg, & Skeie, 2016). The risk increases with age and is even greater if one or both parents are obese.

Inactivity and high energy intake

Weight is influenced by both heredity and environment. At the population level, changes in the environment and lifestyle can probably explain the increase in the prevalence of overweight and obesity over the last decades, and the greatest weight gain is observed among those who are most genetically predisposed to gaining weight (WHO, 2022). We live in a society that encourages physical inactivity, with a wide and tempting range of food, also called an 'obesogenic environment'. These are two factors that increase the risk of overweight and obesity, see the section about prevention below.

Association between mental disorders and obesity

Mental disorders can affect appetite, will and self-control, all of which are important factors for explaining the development of obesity. People who are affected by anxiety, depression and psychoses are also more vulnerable to experiencing stress and helplessness when facing challenges. This can lead to changes in regulation of appetite and satiety and a higher intake of nutrient-poor foods that are rich in fat, sugar or salt.

Population studies among adults show that there is a higher proportion of mental disorders such as anxiety and depression among people with obesity than in the general population (de Wit, 2010). Follow-up studies have shown that anxiety and depression increase the risk of obesity development. However, obesity also increases the risk of anxiety and depression (Berkowitz & Fabricatore, 2011).

Medicinal side effects can also explain some of the association between obesity and mental disorders. Several medicines used for severe psychiatric disorders can affect brain mechanisms that control appetite and metabolism, which can in turn lead to major weight gain. This applies particularly to antipsychotic medicines. However, these medications probably cannot explain all increases in body weight and unfavourable fat composition among people with psychotic disorders, as an increased risk of obesity and metabolic syndrome has also been detected early in the course of these disorders (Thakore, 2004). In addition, it has been shown in large population studies that people with psychotic disorders who use antipsychotics have equally long, or longer, life expectancy than unmedicated people with psychotic disorders (Torniainen et al., 2015). In recent years, hypotheses have suggested that the association between mental disorders and obesity may come from common genetic factors in addition to environmental factors (Bahrami et al., 2020), which makes the picture even more complex.

Overweight and obesity among children and adolescents are associated with poorer health-related quality of life and self-esteem, depression, and emotional states and behavioural difficulties. Self-esteem related to physical appearance seems to deteriorate with increasing age among children and adolescents who are overweight and obese. It is unclear whether psychological disorders and complaints are a cause or a consequence of obesity. There may be other common factors that cause both obesity and psychological conditions among vulnerable children and adolescents (Rankin et al., 2016).

Nevertheless, it is common for children with high weight to experience stigma (Puhl & Lessard, 2020), and weight-related bullying seems to explain some of the association between higher BMI and poorer mental health (Blanco et al., 2020). It is important that health workers and others are aware of using supportive, understanding and non-stigmatising communication with children and adolescents and their families to reduce weight-related stigma (Puhl & Lessard, 2020).

Prevention and challenges

To alter overweight and obesity at society level, both population-focused and individual-focused interventions are necessary. We do not discuss the treatment of obesity in the health service here but refer to the guidelines from the Directorate of Health (Directorate of Health, 2011). To prevent weight gain and obesity, measures at community level are particularly important, not least among those in the population who are most predisposed to gain weight. Such population-oriented measures can have a wider reach and be more effective than individual interventions, such as encouraging individuals to control their weight.

When it comes to diet and physical activity, it has been shown that fibre-rich foods, the "Mediterranean diet", breastfeeding and physical activity including walking reduce the risk of weight gain and overweight/obesity, whereas sugary drinks, energy-rich and nutrient-poor food including fast food and a lot of screen time increase the risk (World Cancer Research Fund International/American Institute for Cancer Research, 2018).

Internationally, there is an increasing discussion about which public health interventions can and should be used to reduce the proportion of overweight and obesity in the population. The World Health Organization's report from 2022 on obesity in Europe (WHO, 2022) describes the following barriers that may prevent or weaken the initiation of community-oriented measures:

- Many claim that it is the individual's responsibility to control their weight, and not the responsibility of society /politicians.

- Measures to address the underlying factors for obesity are often not prioritised.

- Economic considerations often become a priority at the expense of health, including political measures to prevent obesity.

- It is challenging to have measures across sectors of society.

- Measures that affect the food industry often meet major opposition.

Children and adolescents are particularly vulnerable and affected by their surrounding and how their family, childcare, school, and the local community facilitate a healthy diet and physical activity. Population-focused interventions discussed in Norway include facilitating physical activity in schools and the local community and reducing access to nutrient-poor and energy-rich foods such as sugary drinks. Important interventions may include economic tools, marketing regulations, particularly digital marketing targeted at children and adolescents, portion control, changing the recipes of industrially produced foods and developing new products with healthier ingredients, as well as labelling food as healthy with the keyhole symbol used in the Nordic countries, arrangements for a healthy diet in schools and childcare centres as well as media and awareness campaigns, (NIPH, 2017d).

In 2014, the Minister of Health joined a group of stakeholders from the food industry and industry, with an aim to implement measures to improve the diet of the population. This led to an agreement of intent to facilitate a healthier diet, which has now been extended to 2025 (Directorate of Health, 2019).

Norway has also joined the World Health Organization's goals to reduce the incidence of non-communicable diseases in the period 2010-2025. Here, one of the initial goals is to stop the increase in obesity in the entire population. Neither Norway nor other member states have managed to meet this target.

Knowledge base

Data on overweight and obesity in Norway have been taken from various studies, including the Child Growth Study (7-8-year-olds), the UngKan survey (9-year-olds and 15-year-olds), the Youth Growth Study (12-13-year-olds), the Trøndelag Health Study ( HUNT) and YoungHUNT (youth, adults), the Tromsø study (adults), Fit Futures (youth), SAMINOR (adults), the Swedish National Service (young adults), the National Public Health Survey (NHUS) at NIPH, and Statistics Norway. The review of the Tromsø survey and the Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT) is partly based on unpublished data.

In the Child Growth Study, the Youth Growth Study, the UngKan surveys, and the health surveys HUNT, YoungHUNT, the Tromsø survey, Fit Futures and SAMINOR, weight and height were measured by health personnel. The results from such data are more reliable than self-reported data, because in self-reported data, too low weight is often reported. However, self-reported data, for example from the Norwegian National Service, can still be a good source for studying trends over time.