Tuberculosis (TB) in Norway

Article

|Updated

|Tuberculosis is caused by the mycobacterium tuberculosis. The disease usually occurs in the lungs (pulmonary tuberculosis), but can affect all the organs in the body. It can be a serious disease if left untreated, but the vast majority of those who receive treatment recover completely.

Droplet transmission

Tuberculosis is not very contagious compared to many other diseases, and transmission usually requires close contact over time.

Tuberculosis transmission occurs through airborne spread of droplets containing the tuberculosis bacterium from a person with pulmonary tuberculosis.

Outdoor transmission is rare. With a few exceptions, only untreated infectious pulmonary tuberculosis can be transmitted. Tuberculosis that affects other organs, such as the lymph nodes or skeleton, are usually not contagious.

When a person with pulmonary tuberculosis coughs, sneezes, speaks, laughs or sings, tiny infectious droplets or aerosols are released into the air. The smallest droplets can pass mucus and cilia and reach the smallest alveoli when inhaled.

Close contacts, particularly those from the same household, are most exposed to transmission but only a few will become infected. Nevertheless, experience has shown that only half of the closest contacts are infected, including the children of parents with pulmonary tuberculosis.

As a general rule, people with infectious pulmonary tuberculosis must be admitted to hospital and isolated. Once a person with pulmonary tuberculosis has received effective treatment over two weeks, they are no longer considered contagious. The isolation usually ends at this time.

Contact tracing should be performed around each case of pulmonary tuberculosis, see below.

Only a few of those infected become ill

People who are only infected, known as ‘latent tuberculosis’, are not sick and cannot infect others.

Of those who are infected, between 5 and 10 per cent will go on to develop the disease within their lifetime. This usually happens within the first two years after infection. People with latent tuberculosis, who also have other risk factors for developing the disease, will benefit from preventive treatment to reduce their risk. Preventive treatment is voluntary.

There is a greater risk of developing the disease if you have other conditions that weaken the immune system, such as HIV. A weakened immune system as a result of immunosuppressive treatment, for example, for arthritis or in connection with organ transplantation, also increases the risk of developing disease. Young children have a higher risk of developing disease than adults due to their immature immune systems. The youngest children are also at greater risk for severe complications of tuberculosis. Nevertheless, most people who become infected, even in these groups, will not develop the disease.

Symptoms

Pulmonary tuberculosis is the most common form of tuberculosis, but it is also possible to have tuberculosis in the lymph nodes, the skeleton or the peritoneum. Only pulmonary tuberculosis can infect others. Tuberculosis disease usually develops slowly over several months. Common symptoms are:

- prolonged cough (with pulmonary tuberculosis)

- night sweats

- weight loss

- fever

Tuberculosis of other organs will cause symptoms in those organs, e.g., tuberculosis in the lymph glands often causes swollen glands.

Detection of infection and disease

Screening for tuberculosis (latent tuberculosis): In Norway, two methods are used; a skin test (Mantoux) and a blood sample (IGRA). The latter is used mostly.

The Mantoux test is most often performed in public health clinics, and is given as a blister on the forearm, where a tuberculin substance is injected into the skin using a small syringe. The result is read at the clinic after 3 days. The swelling (not the redness) is measured in millimetres. If it measures more than 6 mm it is considered positive.

The Mantoux test gives many false positive results, i.e., the result is positive without infection. Therefore, a positive Mantoux must be confirmed with a more specific test, IGRA (Interferon-Gamma Release Assay), before it can be concluded that the person has latent tuberculosis. The IGRA blood test does not give false positive results as a result of BCG vaccination or infection with other mycobacteria. Today, IGRA is the most widely used screening method. However, it may be easier to perform a Mantoux test among young children than to take a blood sample, and in many places IGRA screening is only available in hospitals. Both methods are therefore useful.

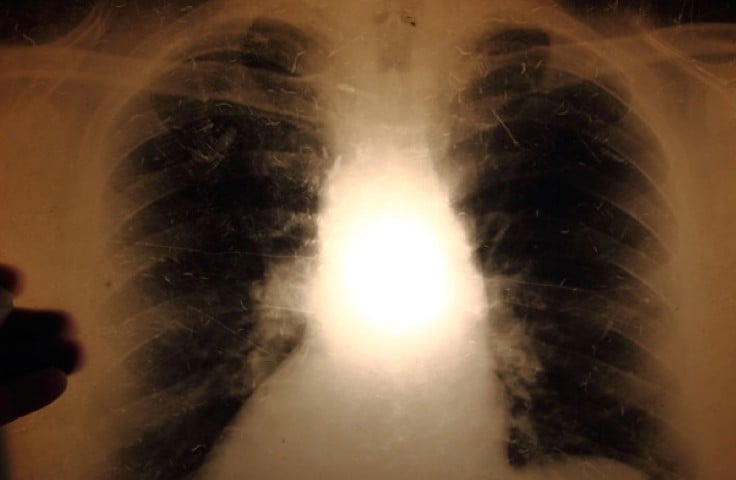

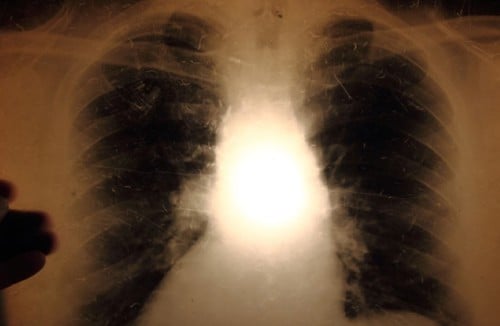

Examination for tuberculosis disease: If the screening for tuberculosis infection is positive, an X-ray examination of the lungs will be performed to detect any tuberculosis disease. A chest X-ray can also be used as a first examination if tuberculosis is suspected, or as part of a screening.

Microbiological examination of secretions from the airways (sputum) or samples from other organs with tuberculosis than the lungs is necessary to confirm a final diagnosis. Such samples include microscopy, genetic engineering examination and bacteriological culture. The studies may indicate the degree of infectivity. If tuberculosis outside the lungs is suspected, other examination methods may also be relevant.

All tuberculosis examinations are free of charge for the person concerned.

Fewer than 300 cases per year

While the incidence of tuberculosis worldwide is still high, the incidence in Norway is declining and is among the lowest in the world. The number of tuberculosis cases in this country has decreased steadily since 2013. Since 2016, less than 300 cases have been registered annually, and in 2019 and 2020, less than four cases per 100,000 inhabitants were registered. All cases of tuberculosis disease must be notified to the Norwegian Institute of Public Health.

Figure 1: Tuberculosis cases in Norway 1990-2020 by place of birth; Norwegian-born (Norskfødte), foreign-born (utenlandsfødte) and total (totalt).

The incidence of tuberculosis among Norwegian-born people is very low, and is even lower among people born in Norway to Norwegian-born parents. Despite an increase in the number of tuberculosis cases among people born abroad since the mid-1990s and until 2013, the incidence among Norwegian-born people has continued to decline steadily.

For people born abroad, the incidence in Norway largely reflects the incidence at their place of birth, and most are assumed to be infected before arrival in Norway. Most of the people in this group who are diagnosed with tuberculosis are young adults, half are under the age of 30 and there is some predominance of men (which corresponds to that seen elsewhere in the world). Among Norwegian-born people, however, the incidence is spread over all age groups, with the majority among those over 60 years of age.

Internationally, drug addicts and homeless people are a risk group for tuberculosis, but few cases of infectious tuberculosis are diagnosed so far in these environments in Norway.

Most tuberculosis cases in Norway occur in Oslo, mainly because it is the largest city in Norway and because there is a higher proportion of foreign-born inhabitants than in other regions. Low numbers within each county lead to some random variations from year to year.

DNA studies of bacteria

In Norway, DNA studies are carried out on all tuberculosis bacteria that have been grown in the laboratory. These genetic tests are also called fingerprint studies. These studies give important information when trying to trace a transmission route.

DNA studies show that there is little transmission in Norway between immigrants and from immigrants to people born in Norway. Some exceptions occur; in 2016 there was an outbreak connected to an education institution in Eastern Norway.

Treatment

Tuberculosis is a treatable disease, and most people recover completely. After two weeks of correct treatment, most people with pulmonary tuberculosis will no longer be contagious. As the tuberculosis bacterium divides very slowly, treatment must normally continue for six months for the medication to kill all the bacteria in the body, which often means long after the patient has finished with symptoms. Only in this way can we ensure that the patient recovers completely. If treatment is stopped prematurely, some bacteria may survive in the body and the disease may return. The bacteria may then have developed resistance to some of the medicines, so that even more types of medicines must be used over an even longer period of time. Treatment of such resistant tuberculosis can take up to two years, and in some cases even longer.

To ensure recovery and to prevent development of resistant bacteria it is very important that all treatment is completed. The World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends that all tuberculosis treatments occurs by having health workers observe patients take their medications every day throughout the treatment period (DOT - Directly Observed Therapy). DOT is used to provide patients with support throughout the treatment period, and to ensure that treatment is completed. The health worker can also give advice about the ongoing treatment and monitor any side effects of the medication.

In Norway, treatment results are good. Tuberculosis is usually a curable disease.

Resistance

Bacteria that have become resistant to the usual drugs are a serious and growing global problem. Multi-resistant bacteria are tuberculosis bacteria that are resistant to both rifampicin and isoniazid, the most important medicines in the treatment of tuberculosis. In the last 10 years, the number of cases of multi-resistant tuberculosis in Norway has been consistently low between four and eleven cases per year. Some countries have more bacteria that are resistant to only one drug.

Patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis may either have been infected with resistant tuberculosis bacteria, or they may have developed resistance as a result of incorrect or incomplete treatment. Multi-resistant tuberculosis must be treated with several types of medication, and for longer than usual, often two years.

Costs reimbursed

Under disease control law, tuberculosis is defined as a dangerous communicable disease. The individual will therefore be recompensed for all expenses for examination, treatment and vaccine. People born outside Norway who are under investigation or treatment for tuberculosis can stay in Norway until treatment is completed.

Groups with a duty to have a tuberculosis examination

Everyone who comes from countries with a high incidence of tuberculosis and who will be in Norway for more than three months (including migrant workers and students) must be examined for tuberculosis. This also applies to all refugees and asylum seekers, regardless of their origin. Refugees and asylum seekers are most often examined while they are at the arrival centre, and the examination must take place within 14 days of arrival. People who come as part of family reunification or as quota refugees are examined in the municipality where they are to be settled. It is the municipality's responsibility to invite to an examination within four weeks of arrival.

People who, during the last three years, have resided for at least three months in countries with a high incidence of tuberculosis, and who will work with children, people in need of care or people who are sick, must also have a tuberculosis examination. It is the employer's duty to ensure that the examination is carried out before starting work. This also applies to students and interns, as well as au pairs. The employer does not have the right to see the actual result of the examination, only a confirmation that the person does not have contagious tuberculosis.

A tuberculosis examination may also be required if healthcare personnel have a justified suspicion that someone has been exposed to a particular risk of tuberculosis infection in another way than the above, or if there is medical suspicion of tuberculosis disease.

Preventive treatment

People who are infected with tuberculosis may be offered preventive treatment to reduce the risk that the infection will later lead to disease.

Contact tracing

When a person has contagious pulmonary tuberculosis, the Municipal Medical Officer will contact people who may have been infected for examination. You will usually start with a blood test (IGRA) or a skin test (Mantoux) as described above. Examination of the social circle of a person who is ill is called contact tracing. The Municipal Medical Officer, often in collaboration with a hospital doctor or the tuberculosis coordinator, will assess who should be contacted. Most often, those who have been most with the patient will be examined first, for example, a partner, children or others the patient has spent a lot of time with. If infection is detected in this group, Municipal Medical Officer may decide whether more people should be examined, e.g., from work, or friends who have been visiting a lot. It takes up to 8 weeks from the time of infection until it appears on the samples, since it takes time for the immune system to react to the tuberculosis bacterium. Therefore, it may be necessary to repeat the examination after 8 weeks in order to rule out any infection.

People who are called in for an examination will not be told the name of the person who is ill, for privacy reasons.

Contact tracing can have two purposes: 1. Find the source of the infection. 2. Find out if the patient has infected others.

Finding the source is relevant, for example, if a child is diagnosed with tuberculosis, because then the infection will have occurred recently. Such contact tracing is relevant for both patients who have infectious and non-infectious tuberculosis.

Determining if the patient has infected others is only relevant with infectious pulmonary tuberculosis. The people that the patients have had contact with are tested and preventive treatment is provided if needed. The experience from Norway shows that it is primarily those who are in close contact with tuberculosis patients over a long time who become infected.

Public plans

All municipalities must have a tuberculosis control programme as part of their Infectious Disease Control Plan. Regional health authorities will have their own tuberculosis control programmes and appointed tuberculosis coordinators.

Notification duty

All cases of tuberculosis must be reported to the NIPH, by regulation from the Ministry of Health and Care Services 2002 (revised in 2009). There are separate rules for the duty of notification.

BCG vaccination

The Norwegian childhood immunisation programme includes the BCG vaccine for children at increased risk of contracting tuberculosis. This recommendation applies to children with a mother or father from a country with a high incidence of tuberculosis. They should preferably be vaccinated as newborns. Many of these children have a higher risk of transmission in their immediate environment than other children in Norway. Their families may travel on longer visits to their homeland, where the risk of tuberculosis transmission is higher.

In addition, BCG vaccine is recommended for people at particular risk:

- people who will stay in countries with a high incidence of tuberculosis for more than three months and have close contact with the local population. This may apply to people who will work with humanitarian aid, in health services, prisons or in other vulnerable environments in these countries.

- health personnel in the specialist health service who over time (approximately 3 months) will work with adult patients with infectious pulmonary tuberculosis or culture of mycobacteria in a microbiological laboratory.

More about BCG vaccine, see below.

BCG vaccine

The tuberculosis vaccine (BCG vaccine) consists of live, attenuated bacteria, Bacille Calmette Guérin. The vaccine is injected. About 80 % of those vaccinated achieve protection against tuberculosis and the effect occurs 6-12 weeks after vaccination. The vaccine is effective in protecting against the severe forms of tuberculosis that can affect children in the first year of life. The duration of protection beyond 10 years is little studied. There is no evidence that people who have been vaccinated have any benefit from booster vaccination. The vaccine has not been shown to be effective among those older than 35 years.

BCG vaccine is one of the world's most widely given vaccines, but is hardly used in low-prevalence countries, such as in Western Europe. See the section above on preventive measures for information on target groups for BCG vaccine.

Testing before BCG vaccination

If infection exposure is unlikely, IGRA, Mantoux test or lung X-rays are not required prior to BCG vaccination. People infected with tuberculosis have no benefit from BCG. It is not dangerous to vaccinate someone who has already been vaccinated or infected, but it can lead to faster and more intense local reactions.

No longer general BCG vaccination in Norway

BCG vaccine was included in the Norwegian childhood immunisation programme in 1947 and was usually given at the age of 14. Until 1995, BCG vaccination was required by law, after which the vaccination became voluntary. BCG vaccination of adolescents with a low risk of tuberculosis ceased after the school year 2008/2009.

When general BCG vaccination was discontinued in Norway, the use of BCG vaccine had been under consideration for a long time. Most Western European countries had discontinued BCG vaccination for people at low risk for tuberculosis. Sweden discontinued in 1975, the United Kingdom in 2005, Finland in 2006 and France in 2007. In the United States, the BCG vaccine has never been used for people at low risk for tuberculosis.

A lot of data have gradually been obtained which shows that targeted vaccination of risk groups may be more appropriate than general BCG vaccination. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Tuberculosis Union - IUATLD have set criteria that should be met before a country discontinues general BCG vaccination. Norway meets all the criteria.

When the current recommendations for BCG vaccine were evaluated in February 2018, it was found that there has been no increase in tuberculosis among groups that were covered by advice on general vaccination until 2009.

Analysis and registries at the NIPH

The NIPH is responsible for the Norwegian Surveillance System for Communicable Diseases (MSIS) which includes the tuberculosis registry and gives advice about measures to prevent and limit infectious diseases.

Vaccinations and any unwanted effects are registered in the Norwegian Immunisation Registry (SYSVAK). The NIPH distributes the BCG vaccine and tuberculin for testing in Norway.

The national reference laboratory at the NIPH receives strains of all newly diagnosed cases in Norway. Identification, genetic typing, resistance determination and freezing of all of these bacterial strains are carried out.